I’ve decided to abandon, or at least postpone, my plan to charge for a subscription to Phlit. The two people who purchased a subscription have had their money refunded, and their names will be inscribed in marble in the Phlit Hall of Fame.

I recently finished a wonderful book: A Little History of the World, by the renowned art historian E. H. Gombrich. It’s intended for youngsters, but it has much to offer adults, too. It’s a concise summary of world history, it’s highly readable, and it provides enough detail/anecdote to enliven the narrative. And it has been approved by a consensus gentium; it has been a worldwide bestseller since its publication in 1936. Gombrich’s Story of Art is also intended for young people, and has also been very popular.

I saw a movie called Amélie (Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain), one of the most popular French movies of recent years. I was disappointed: it seemed to be an unending series of isolated scenes/insights/witticisms, lacking drama, development and broad themes. It was a jumble of isolated pieces, isolated atoms, rather than an organic whole. Should we speak of the atomization of art?

I also saw a movie called Master and Commander (2003). A good recreation of Napoleonic naval history, enjoyable to watch. Perhaps too many isolated incidents, though, and not enough sustained development.

And finally, I saw the highly popular movie, Akeelah and the Bee. Good stuff, great for a family audience. About a ghetto girl who achieves Spelling Bee glory. No isolated incidents, everything is a part of the whole — organized rather than atomized. It points out that spelling is trivial compared to literature. Surely it has been shown to inner-city students, but with what effect? Can it change culture? Can it inspire ghetto students?

My account of my trip to England now has photos. Hope you’ll take a look.

My wife and I recently returned from a ten-day trip to France — our first Europe trip since ’96, when we went to Italy. At first, we thought of going to Munich and Prague, but the flight was surprisingly expensive, and we had no appetite for planning a complex trip. When we looked at Paris, it seemed a bit cheaper, and it also seemed simple — with one click of a mouse, we could book a flight and a hotel for ten days. Later, however, we had second thoughts about spending all of our time in Paris; we decided to rent a car, and spend four days in Chartres and the Loire Valley; we planned to find lodgings as we went. Eventually, we’d like to go to Munich and Prague since my wife is studying German, since we’d like to visit the Alps (Munich isn’t far from the Alps), and since Prague seems to be a place of cultural ferment — one might compare it to Paris in the 1920s.

We tried to go as late in August as possible, thinking that the weather would be cooler, and the crowds smaller. While these expectations turned out to be true, there was also a downside to August: August is vacation time in Paris, and perhaps in France generally, so many things were closed. Often we walked to a restaurant or shop that had been recommended by our guide-book, only to find a sign in the window, “Closed During August — Bonnes Vacances à tous!” But July and early August are crowded and hot, so if you must go during the summer, late August may be the best time.

Traveling is difficult; if you’re expecting non-stop fun, you’ll be disappointed. Traveling involves many inconveniences, and you may find yourself wondering, “What are we doing here? What did we pay all that money for?” But it’s an adventure, an experience, and you may enjoy looking back on it, even if it was difficult while you were there.1 I’ll never think of France the same way; from now on, whenever I read about France, I’ll feel a connection; France is no longer a completely foreign country. (On my last day in Paris, I was pleased when a man from Italy asked me for directions.) My trip to France made me eager to study the French language, French history, etc., and it gave me a positive impression of the French people.

The people were always courteous, and often friendly. For example, when we were returning our rental car in Paris, we weren’t sure of our way, and stopped to ask directions. The man we asked (a FedEx driver) drew us a diagram, and spent lots of time explaining how to reach our destination.

The people were scrupulously honest in business dealings. I was cheated once in England, and repeatedly in Italy, but never in France. Once we bought lunch on the street, and took it inside, unaware that the price is higher when you sit down than when you “take out”. Later we questioned the bill, and the cashier, instead of arguing with us, let us pay the smaller amount. As we walked away, we felt we had underpaid, so we came back and bought something else.

Another time, we bought a baguette (a long, thin loaf of French bread) for 1.10€ (the French have switched from the Franc to the Euro; 1.10€ is equal to about $1.40). We paid 2€. Instead of making .90€ change, the cashier just handed us 1€. The French aren’t as interested in money as we Americans are. Have you ever known an American cashier to sacrifice $.10? Would an American close a big restaurant, in a high-rent neighborhood, for the whole month of August, so he could take a vacation? Economists may criticize the French economy for its sluggish growth and high unemployment, but perhaps a bit of socialism makes people more relaxed, and less intent on profit.

When I was in Hong Kong, in ’98, I ordered a couple things at a restaurant, and was surprised when the man gave me a third thing — something I hadn’t ordered, but was glad to have. This is a common practice in France — when you buy a couple things, you receive something else for free. When we went to a health food store called Naturalia, they charged us for two items, and didn’t charge us for a carrot. Next time we went to that store, we bought sesame spread (they don’t eat much peanut butter), and the cashier asked if we needed bread, probably willing to give us a free loaf. I didn’t expect such generosity, and wasn’t prepared for it. I’m accustomed to cashiers asking questions designed to sell something, not designed to give something away. If an American is asked, “Would you like a drink with that?” he assumes that the cashier is trying to sell him a drink, and doesn’t realize that a French cashier may be offering him a free drink.

If you’re looking for gifts, try “the heavenly hub, a small chain of religious stores on a cobbled street in Paris beside the ancient Church of Saint-Gervais, about a five-minute walk from Notre Dame.... Monastica and Produits des Monastères.”

We flew to Paris on August 13, shortly after the “Liquid Bomb” plot. The lines in the airport were long, and our flight was way behind schedule. Finally we reached France — a country I had heard about, and read about, all my life, but had never been to. We took a train into Paris, then a subway to The Bastille. Our hotel was called Classic Bastille, but it actually wasn’t close to The Bastille, and The Bastille itself isn’t in the center of the city (before it became a famous prison, The Bastille was part of the wall that circled Paris, it was peripheral, not central). The Internet had led us to believe that our hotel was central, but that wasn’t the case; it was even less central than The Bastille, it was east of The Bastille, on Rue de Charonne, in the 11th Arrondissement, in a rather drab neighborhood. The moral of the story: don’t reserve a hotel room until you’ve looked at a map, or at least looked at a guide-book.

|

|

Below is the same map in GoogleMaps version:

|

We finally reached our hotel at noon on August 14. We hadn’t slept much the previous night, but we wanted to explore Paris, so we walked back to The Bastille, unencumbered by baggage. When we were in Venice, we had used a book on “walks in Venice”, and we had a similar book for Paris. The book took us through the highlights of The Marais, starting at The Bastille, and walking east. We saw the Hotel de Sully, the Place des Vosges, and a section of the original city wall, the wall of Philippe Auguste, built around 1200. During the early history of Paris, The Marais was undeveloped, marshy, peripheral, but it became fashionable around 1600. The Hotel de Sully and the Place des Vosges both date to around 1600. The Hotel de Sully has statues representing the four seasons and the four elements. The Place des Vosges is closed to cars, so it’s quieter and pleasanter than many Paris plazas. The scale is friendly and human, unlike those enormous plazas that seem designed for giants, or giant crowds, rather than for people.

|

|

| Statues of Autumn and Winter -- Hotel de Sully. Autumn (the statue on the left) is holding grapes, symbol of harvest-time, and above him are the scales of Libra; Libra is an autumn zodiac sign. Winter is an old man, above whom is probably Capricorn, a winter sign.

|

|

| Place des Vosges

We enjoyed exploring not just the main streets of The Marais, but also its back streets and narrow alleys. In the 19th century, the city planner Haussmann demolished many narrow streets so he could construct broad avenues. One wishes that Paris had more narrow medieval streets, and fewer broad avenues; one wishes that Paris were more pedestrian-friendly, and less car-friendly, less Haussmannized. There are still, however, many narrow streets in Paris, and many pedestrian-friendly streets. Another complaint that one might make about Paris is that many of the buildings are designed to be grandiose, designed to impress. Medieval cathedrals were grand, but their grandeur exalted God, not man. Many Paris buildings are designed to exalt man — Napoleon’s tomb, for example, or The Pantheon. They’re grandiose rather than beautiful; they have little aesthetic merit. As for the Eiffel Tower, it’s merely an engineering curiosity, and perhaps not even that. Compared to an American city, though, Paris is full of history, full of striking, handsome buildings, and well preserved. Most remarkable is the height of Paris: there are virtually no skyscrapers, so the old buildings aren’t in the shadows, they still stand tall. Skyscrapers have been relegated to a business district east of Paris, called La Défense; the only exception is the Tour Montparnasse (Montparnasse Tower), a modern skyscraper from the top of which tourists can get a view of the city. Perhaps there are three approaches to traveling:

While I was in France, I suppose I took all three of these approaches, at various times. If you attempt the third approach, you may find it difficult to keep your own center, since you’re hustling around the city all day, pulled out of yourself by all sorts of things. Here’s what I recommend: do some sitting meditation in every church you visit. Churches are excellent places for meditation — the chairs are firm and straight, it’s quiet, and it seems like an appropriate activity in that environment. Doubtless many people will think that you’re praying. In fifty years, when meditation becomes more widespread, and prayer less so, perhaps churches will be dedicated to meditation, or perhaps they’ll put up signs, “Prayer Only — Meditation Forbidden”. I’m probably mistaken, though, when I speak of prayer and meditation as if they were separate and distinct; doubtless they’re overlapping and related. If it’s difficult to keep your own center while traveling, it’s also difficult when you get home from your trip. When you get home, you’re no longer hustling around Paris, but you’re hustling around to do all the things that were left undone when you were away. After a trip, one often feels low. Perhaps an interesting essay could be written on the subject of The Return Home. On August 15, we walked to a cemetery called Père Lachaise, which was in the general area of our hotel. It’s a jumble of 70,000 graves, many of which are falling over. Since we didn’t have a map, we were hard put to find specific graves. Eventually we managed to find Proust, Wilde, Chopin, and Balzac. We also saw Bellini’s grave, but we couldn’t remember what he was famous for. Then we took the subway to the old opera house, which is known for its opulent, ornate architecture. From there, we walked south, aiming for the Eiffel Tower. We passed through the Place Vendôme. Unlike the Place des Vosges, the Place Vendôme is open to cars — or perhaps I should say, ruined by cars. Like many Paris sights, the Place Vendôme has been changed by France’s political changes, and its history reflects France’s history.

|

|

| The old opera house (Palais Garnier)

Laid out in 1702, the Place Vendôme originally had an equestrian statue of Louis XIV. Around 1805, Napoleon replaced this statue with a column patterned after Trajan’s Column in Rome; at the top of the column was a statue of Napoleon. When Napoleon was exiled in 1815, and the monarchy was re-established, the statue of Napoleon was remodeled as a statue of Henry IV. But when the Bourbon kings were ousted in 1830, Napoleon was re-instated on the top of the column . In 1871, at the time of the Commune, the whole column was knocked down, at the suggestion of the painter Gustave Courbet. Later in the 1870s, however, the column, topped with a statue of Napoleon, was rebuilt, and Courbet was fined.

|

|

| Place Vendôme

The figure at the top of the column now is doubtless Napoleon, but only a person with binoculars could render an opinion on the statue, or on the column’s reliefs. Perhaps only the person who made the reliefs knew them in any detail, or cared about them; to everyone else, they’re just something big, grand, Roman-Napoleonic. During the 19th century, France was torn between the monarchical party and the popular party. Within the monarchical party, there was a division between the Bourbon branch and the Orleans branch. Within the popular party, there was a division between working-class radicals and middle-class moderates. To complicate matters still further, there was the legacy of Napoleon, and the descendants of Napoleon; this Napoleonic element was neither purely monarchical nor purely popular, but rather a little of each. The Place Vendôme was affected by all these currents and cross-currents. After passing through the Place Vendôme, we followed the Seine to the Eiffel Tower, arriving just in time to join a bike tour called Fat Tire; our guide-book spoke highly of Fat Tire. After all the walking we had done, it felt great to be on a bike. When the tour was finished, though, we realized that we had only seen a few sights. We hadn’t explored any back streets, and we hadn’t reached peripheral places like the Bois de Boulogne (the big park on the west edge of Paris), or Montmartre (the hilly area on the northern edge of Paris, known for windmills, the Sacré-Coeur basilica, etc.). Though the tour lasted more than three hours, much of the time was spent preparing the bikes, sitting at a café in the Tuileries, etc. The commentary that accompanied the tour left much to be desired. And the tour was expensive to boot. One of the stops on the bike tour was the Place de la Concorde, an enormous square on the banks of the Seine, known as the site of executions during the French Revolution. In the center of the Place de la Concorde is an obelisk that was built in Egypt around 1200 BC, and brought to France in 1829. Around the periphery of the Place are eight statues honoring major French cities (Lille, Strasbourg, Lyon, Marseille, Bordeaux, Nantes, Brest and Rouen). In 1870, when France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War, the Germans took Strasbourg. The Strasbourg sculpture in the Place de la Concorde was in mourning until 1918, when France’s victory in World War I brought Strasbourg back to France. Since Louis XIV seized Strasbourg in 1681, Strasbourg and other northeastern cities have been a bone of contention between France and Germany, and an issue in numerous wars. One might suppose that Paris is full of American tourists, but in fact, we encountered very few Americans, and rarely heard any language but French spoken around us. On the bike tour, however, we encountered several Americans. Like us, they were struck by the fact that French showers have little or no curtain, so the water spills onto the floor of the bathroom, try as you might to keep it within the tub. Perhaps the French take baths rather than showers, or perhaps they shower sitting down, holding the shower-head in their hand. Why do Germans and Scandinavians study English so assiduously, while the French have little eagerness to learn English? We met scarcely a single Frenchman who spoke good English, but when we met a German family, even the young children could understand us. When we needed to communicate with a Frenchman, we spoke clearly, and we instinctively believed that he would understand us, if only we spoke slowly, repeated ourselves, etc. Meanwhile, the Frenchman had the same instinctive belief: he believed that if only he spoke French distinctly, eventually it would get through our thick heads. So we went back and forth, back and forth, both of us ignoring the strange sounds that the other person was making, both of us refusing to believe that our own straightforward words could fail to get through. When the bike tour was over, we took the subway home. We usually rode the subway twice each day. The Paris subway is fast, clean, and safe. I can’t help thinking, however, that there’s a better way to travel. If I go to Paris again, I’m going to bring a small, folding bike, or better yet, a pair of roller blades. Of course, if you have a centrally-located hotel, you don’t have to travel as much. [Update 2018: Like most major cities, Paris now has a bike-share program, so I won’t need roller blades on my next visit.] The mannerisms of the French are quite different than those of Americans. They look at you with a fixed glance that’s neither friendly nor unfriendly. What do they think of our mannerisms? They probably think that our glance is saying, “I’m a friendly person, I like you, you should like me.” Perhaps our Protestant heritage makes us think of all men as our brothers, all women as our sisters. On the other hand, the Catholic heritage of the French may make them treat people as strangers, outsiders; their glance seems to say, “I have no connection with you. Why should we pretend to have friendly feelings for each other?” I remember seeing a French woman, about 65 years old, walking along the sidewalk in such a businesslike, serious, determined way that it seemed she would walk through a brick wall if she encountered one. Other human beings mattered little to her; she was focused on her own affairs. Some people complain that the French are cold, reserved, unfeeling. When we were in Paris, we were struck by the large number of minorities. Although one often hears that France has a large Arab population, we were struck by the large number of blacks and Asians. An interesting question is, “do minorities in France acquire the mannerisms, the glance, that Frenchmen have?” A study of French mannerisms should consider the adoption of these mannerisms by people who immigrate to France. Most of the Asians in Paris seem to come from China; while some of them live in Paris, others seem to live in the provinces, and come to Paris as tourists. Like New York, Paris has many Chinese restaurants. Blacks in Paris seem to maintain African roots, and African dress; they seem to have left Africa more recently than American blacks. Since they haven’t had time to mix with whites, their complexion is often “pure black”, unlike the complexion of many American blacks. Just as the French have certain characteristic mannerisms, so too they have certain characteristic physical traits. They seem to be better-looking than other nationalities. They have high cheek-bones, and a long, narrow face, whereas East Europeans seem to have a wider, more rounded face. The problem of obesity, much-discussed in the U.S., doesn’t seem to exist in France. Perhaps the lower level of stress in France results in a lower rate of obesity; people who are relaxed are less likely to over-eat, while people who are stressed use eating to lower stress. Around 1800, the English became known for their style of gardening; the so-called “English garden” was free, wild, natural. The French, on the other hand, were known for their clipped, controlled, formal gardens. This is still true today: everywhere we went, we found not only plants but even trees that were carefully trimmed. On August 16, we went to Notre Dame, famous for its twin towers, for its location in the heart of Paris on the Île de la Cité, for its prominent place in the works of Victor Hugo and other French writers, and for its vast age and its vast size. Notre Dame is swarming with tourists; it’s one of the sights that every tourist feels he must see. We were swept inside the cathedral by a river of humanity. As with most cathedrals, you enter on the west, and walk toward the altar, which is on the east side; thus, the holiest place in the church is on the side of the rising sun.

|

|

| Notre Dame

After entering the cathedral, we were delighted to find some young people offering free tours in a variety of languages; they were part of an organization called Casa, which has chapters in about twenty French churches. It was a great tour, one of the highlights of our trip to France. Each sculpture and each window has a story to tell, and I love hearing those stories. The crush of tourists is a drawback, though, so I recommend that you contact Casa in advance, and ask them for a quiet hour. Our guide pointed out that, in the south rose window, the apostles are depicted sitting on the shoulders of the prophets, to illustrate how the apostles drew on the work of the prophets. One is reminded of Newton’s famous remark, “If I have seen further, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.” After Notre Dame, we went to Sainte-Chapelle, which is also on the Île de la Cité. While Notre Dame was begun in 1163, Sainte-Chapelle was built by Louis IX (Saint Louis) in the 1240s. It was designed as a private chapel that the king could enter from his palace (later kings used the Louvre as their palace, or the chateau at Versailles); compared to Notre Dame, Sainte-Chapelle is very small. While Notre Dame took two hundred years to complete, Sainte-Chapelle took just two years to complete. Saint Louis used Sainte-Chapelle to hold the relics that he had acquired, such as the Crown of Thorns. (Likewise, Chartres Cathedral claims to possess the cloak of the Virgin Mary, and other churches claim to possess other relics.) Today Sainte-Chapelle is known not for its relics but for its stained glass, which some connoisseurs regard as the finest in France. Alas, there’s no tour guide; Sainte-Chapelle’s lips are sealed.

|

|

| Sainte-Chapelle

From Sainte-Chapelle, we walked to the world’s largest and most famous museum, The Louvre. I asked where I might find paintings by Claude Lorrain, and I was told to go to “French Painting.” We looked at lots of French paintings, but we couldn’t find Claude anywhere. Claude was a favorite of Nietzsche’s. Claude inspired Dostoyevsky’s dream of an ideal world, and he inspired Dostoyevsky’s remark, “beauty will save the world”.2B Claude painted landscapes and seascapes that glorify the world — not the contemporary world, but rather the Greco-Roman world, or perhaps I should say, the rustic side of the Greco-Roman world. Though he concentrates on nature, his paintings almost always include classical buildings, or classical ruins. His favorite subject was open country with a wide horizon and a big sky; under this sky were usually shepherds and their livestock, and ruins. One might say that Claude illustrates pastoral poetry — Vergil’s Eclogues, etc. Claude depicts the pastoral ideal. When the painter Corot went to the Louvre, he would gaze at Claude’s paintings until the attendants asked him to move on, but they didn’t have to ask me to move on, because I never found any of Claude’s paintings.

|

|

| Claude Lorrain, Seaport, 1674

Ruskin was somewhat critical of Claude. Ruskin was a champion of the English painter Turner, and Ruskin argued that Turner’s landscapes were truer than those of Claude and his school; according to Ruskin, Turner’s trees were more like real trees, his rocks more like real rocks, than Claude’s were. Turner’s nature is majestic, mighty, powerful (according to Ruskin), but Claude’s nature is merely picturesque. Ruskin thought that Turner compared favorably with the Old Masters, but nonetheless Ruskin had some respect for Claude. “A gift was given to the world by Claude,” Ruskin wrote; “He set the sun in heaven, and [was] the first who attempted anything like the realization of actual sunshine in misty air.”3 Claude was perhaps the most popular painter in Ruskin’s England, so when Ruskin raised doubts about Claude, he was doubting the Highest and Mightiest. Turner himself didn’t seem to share Ruskin’s doubts about Claude; Turner always had a high opinion of Claude. It was probably his passion for Claude that inspired Turner to become a painter, and in his will, Turner stipulated that one of his own paintings hang next to one of Claude’s in the National Gallery. Claude is profoundly un-modern, and the modern spirit rejects Claude in the harshest way possible — it ignores him. My sister, who is an artist and a teacher of modern art history, who majored in art in college and earned a Master’s in art, had never heard of Claude until I mentioned him to her. Claude was admired as long as the Greco-Roman ideal inspired Western civilization, but in the 20th century, the Greco-Roman ideal died, and with it Claude’s reputation. I’m fond of Claude because my taste is profoundly un-modern, my work is a throwback to 19th-century culture, I share the ideals of Nietzsche and Claude.

Finally we abandoned the search for Claude, and saw the Louvre’s most famous works, the Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, and Michelangelo’s Slaves. The highlight of our visit was an empty table under the glass pyramid, where we rested and snacked on bread, beer, chocolate, etc. As night approached, we headed back to Notre Dame, where a movie was being shown (movies are becoming common at cathedrals, as are sound-and-light shows, which the French call son et lumière). After the movie, we walked around the Seine, and took some photos of Paris at night.

|

|

| Statue of Henry IV, on the western end of the Île de la Cité.

On August 17, we visited the Arc de Triomphe. Though it’s clogged with traffic, and though its aesthetic merit is questionable, I found it interesting, even touching, as a war memorial, and a focal point of French history. Like Arlington Cemetery, it has a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, where a flame always burns. The Arc de Triomphe is at the center of a square called Place de l’Étoile (Star Square); numerous streets, including the Champs-Élysées, radiate out from the Place, like rays of light from a star.4

|

|

| The eternal flame and the tomb of the Unknown Soldier Here Lies A French Soldier Died For His Country 1914-1918 (Ici Repose Un Soldat Français Mort Pour La Patrie) Many Paris streets are named after Napoleonic battles — Friedland, Wagram, Jena, etc. Many other Paris streets are named after literary or political figures — Victor Hugo, Dickens, Talleyrand. My favorite street name is Rue du Chat qui pêche (the cat who fishes); it’s the name of a tiny street on the Left Bank, just west of Notre Dame.5

|

|

| Rue du Chat qui pêche. I’m reading one of the plaques that are scattered all over Paris. Unfortunately, these plaques are in French, so I could only read them with difficulty.

From the Arc de Triomphe, we walked across the Seine to the Invalides, where Napoleon is buried. More precisely, Napoleon is buried in the Église du Dome, part of the Invalides complex; the complex was begun by Louis XIV, to serve the needs of wounded veterans (invalids). On our bike tour, we were told that, during World War II, allied pilots who had been shot down were hidden in the dome (the dome over Napoleon’s coffin) by the French Resistance; in June 1940, when Hitler visited Napoleon’s tomb, allied pilots were hiding in the dome, close to Hitler. As we toured the Église du Dome, we listened to a recording, which described the highlights of the site. If we tried to rewind the recording, it became confused, and stopped working. Nonetheless, this device added much to our visit, and we were glad that we visited Napoleon’s tomb. When we left the tomb, we took a quick look at the Museum of the Army, which is also part of the Invalides complex; this museum is known for its collection of medieval armor. Before retiring for the day, we went to an upscale restaurant, Square Trousseau, not far from our hotel. As a birthday present, my sister had given me a fancy dinner; she recommended this restaurant. When we got there, however, it was closed — not closed for August, like many other Paris restaurants, but closed until later in the evening. The French don’t go to restaurants until at least 7:30, so restaurants are often closed until at least 7. So we reverted to our usual fare: take-out food, fast food, and supermarket snacks. On August 18, we went to everybody’s favorite Paris museum, the Musée d’Orsay, which is on the banks of the Seine, in an old train station; it’s known for its Impressionist works. We enjoyed exploring the museum on our own, and we also enjoyed using an audio guide. But best of all was listening to a guide who walked around the museum, stopping at works that illustrated the development of Impressionism, such as Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass. The guide was excellent, and spent ample time on each work; this tour was one of the highlights of our trip.5B From the Musée d’Orsay, we walked to one of the oldest churches in Paris, St-Germain des Prés. The neighborhood around the church has some famous cafés, such as Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots. From here we walked east along Rue St. André des Arts, eventually reaching two charming old churches, St. Severin and St. Julien le Pauvre. This was perhaps the best walk we had in France; we felt that we had finally reached the old streets of the Latin Quarter. Near St. Julien le Pauvre is the Hotel Esmeralda, everybody’s favorite budget hotel. And around the corner, on the bank of the Seine, is Shakespeare & Company, the famous English-language bookstore that published Joyce’s Ulysses in the ’20s. (In the early 1900s, it wasn’t unusual for a bookstore to publish a book; Proust’s first book, Pleasures and Days, was published by Calmann Lévy’s Paris bookstore.) Shakespeare & Company has a great location, and it does a brisk business. It tries to be more than a business, it tries to be a center of literary life, and it tries to help aspiring writers with housing, etc. The next morning, we checked out of our hotel, picked up our rental car, and headed for Chartres, about 55 miles southwest of Paris. We wanted to visit the famous cathedral at Chartres, then continue on to “Proust Country” (the town of Illiers-Combray), and the Loire Valley. A short-term car rental is expensive, and the cost of gas and tolls is very high compared to what an American is accustomed to. Nonetheless, we never regretted renting a car. We enjoyed seeing the country between Paris and Chartres. There were no American-style suburbs, and there was more farmland than I’ve ever seen in the northeastern U.S. Chartres Cathedral is an impressive sight indeed. It sits on the top of a hill, and dominates the surrounding country, with its two towering spires, one taller than the other. But before we reached the “old city” near the Cathedral, we saw a sign for a youth hostel (Auberge de Jeunesse), and decided to have a look. It seemed okay, so we took a room for the night. Our room faced the Cathedral, but since we couldn’t open the louvers on our window, we could see only tiny slivers of the outside world; one might say that we saw the Cathedral not face to face, but through a louver, darkly.

|

|

| Chartres Cathedral, west side

The town of Chartres, like other medieval towns, was designed for defense against Vikings and other enemies. It defended itself with its elevated situation, with a small river (the Eure), and with a wall, parts of which are still visible. Tours of the old city are available through the Chartres tourist office. For centuries, Chartres has attracted pilgrims, who are drawn by its relic (the cloak of the Virgin). Even today, pilgrims make the three-day trek from Paris to Chartres. A big hostel near the Cathedral accommodates the pilgrims; if I visit Chartres again, I’d like to try this hostel, and its spacious cafeteria. There’s much to see in the Cathedral — the crypt below, the bell tower above, the choir screen, the sculptured entrances and, of course, the stained-glass windows. Being a connoisseur of cicerones, I looked forward to hearing Malcolm Miller, who has been conducting English-language tours of Chartres Cathedral since 1958, and has written several books about the Cathedral. But alas, he too was taking an August vacation, so I had to settle for an audio tour. I chose a tour of the choir screen, which depicts the life of the Virgin, from the annunciation of her birth to her assumption into heaven. On August 20, we chatted with a German family while eating breakfast. My wife (Yafei) has been studying German, so she enjoyed practicing, and the German family was glad of an opportunity to practice their English. The two children had probably studied English for years, but never met someone who spoke nothing but English. Meeting foreigners is one of the chief pleasures of traveling. After checking out of the Auberge de Jeunesse, we headed toward Illiers-Combray, about 25 miles southwest of Chartres. This town had always been known as Illiers, but since Proust referred to it as Combray, the town changed its name to Illiers-Combray, perhaps to attract tourists. Illiers was on the route that pilgrims took to reach Santiago de Compostela, in northwestern Spain. In English, this route is known as “The Way of St. James”; in Spanish, it’s known as “Camino de Santiago”; in French, it’s known as “Chemin de Saint Jacques.” It has long been the chief route of European pilgrims. Today, the Spanish section of the route is popular with bikers and hikers. As for Proust himself, the only pilgrimages he took were “Ruskinian pilgrimages” — that is, visits to the cathedrals that John Ruskin wrote about. Ruskin was one of Proust’s favorite writers. The symbol of the Way of St. James is the scallop shell. Since Illiers was on the Way, bakeries in Illiers made cookies in the shape of a scallop. These cookies (or “madeleines”) figure prominently in Proust’s work; when he eats one as an adult, its smell and taste remind him of his boyhood in Illiers, and the past suddenly comes alive for him. As Schopenhauer wrote, “Smell might be called the sense of memory, because it recalls to our mind more directly than anything else the specific impression of an event or an environment, even from the most remote past.”6 We enjoyed the drive to Illiers. We enjoyed the freedom of stopping at whatever sight took our fancy. We thought of Proust’s family approaching Illiers by train, and looking for its church spire, as we were doing now. Again we noticed the lack of suburbs: everything we passed was either open farmland, or clusters of small houses. When we reached Illiers, there were few tourists around. We visited the church, which was empty and quiet. It was one of our favorite French churches — until we learned that much of the interior was 19th-century restoration. Proust satirized the Illiers pastor for being fond of modernizing; he makes the pastor say, “I admit there are a few things in my church that are well worth a visit, but there are others that are getting very old.”7 We visited the Proust museum, which is in the house where Proust summered as a boy. The furnishings are interesting — much the same as they were in Proust’s day. There are innumerable photos of Proust and his friends. Alas, the cicerone is mediocre and speaks little English; if you call ahead, however, you may get an English tour. One photo shows Proust with his high-school classmates. Proust is in the middle row, on the extreme left, tilting his head toward the center, lest he be omitted from the picture entirely. I recognized him as much by his peripheral position as by his physical appearance: the intellectual is by nature peripheral.

As a student, Proust didn’t fit in socially; one of his classmates later wrote, “There was something about him which we found unpleasant. His kindnesses and tender attentions seemed mere mannerisms and poses, and we took occasion to tell him so to his face. Poor, unhappy boy, we were beastly to him.”8 Here’s another picture of a tilting Proust, age 25.

And then there’s this well-known picture of a tilting Proust:

Shortly after I saw the photo of Proust with his high-school classmates, I stumbled across a group photo of E. M. Forster and his friends (see below). Like Proust, Forster was on the edge of the group (the right edge), head tilted.

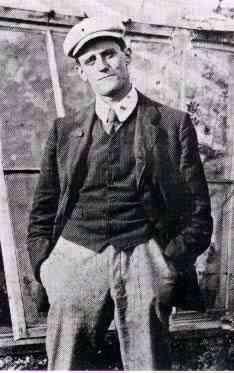

Perhaps one of the chief characteristics of the intellectual is a weak ego, and perhaps this weak ego manifests itself in a posture that isn’t erect, but rather tilted. Below is a tilting James Joyce.

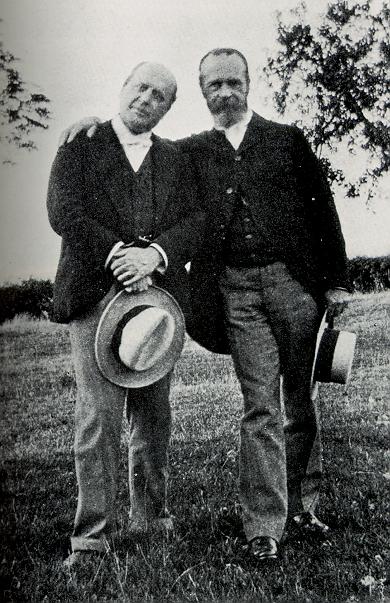

Below is a tilting Henry James, with his brother William.

Below is another tilting Henry, and another erect William.

I suspect it was a weak ego that prompted van Gogh to sign his paintings with his first name, Vincent, as if he couldn’t stand erect in the world of painters. I don’t know of any group photos that include van Gogh, but if there were one, I doubt van Gogh would be in the middle. Isn’t it ironic that the people who are peripheral during their lifetime, the people whom we treat in a “beastly” way, are the very people whose homes we visit after they’re dead? At lunchtime, we walked to a park called Pré Catelan, which had been built by Proust’s uncle, an avid gardener, before Proust was born. On the way to the park, we passed a puzzling structure next to a small pond; we wondered if it was some kind of dock. Later, I learned that it was an old-fashioned laundry station, a place where people could work at water level, and use the river for clothes-washing; before there were washing machines, there were rivers. The street leading to the park was named after the “laundromat”: Rue des Lavoirs. We saw similar laundry facilities along other rivers, in other towns. (All sorts of details about Illiers can be found in George Painter’s biography of Proust; chapter two is called “The Garden of Illiers.”) After lunch, we drove to Bonneval, a small town about 15 miles southeast of Illiers. We noticed that bikes and motorcycles are popular in France, perhaps because gas is so expensive that people avoid driving cars. Bonneval is an old, scenic town built on a river. It has an abbey with a rich history, but the abbey has become a mental hospital, and is off-limits to tourists. And of course, Bonneval has an old church.

|

|

| Bonneval

Since Bonneval doesn’t attract lots of tourists, the people aren’t accustomed to seeing strangers, they’re accustomed to seeing only familiar faces; I thought I detected a certain hostility in their attitude toward strangers. Later, when I read Painter’s biography of Proust, I found that Painter encountered some hostility when he was in Illiers, researching his Proust biography: “When a visitor passes,” Painter wrote, “however unobtrusive his appearance, all pause to stare in amazed hostility, with something of the emotion felt by Aunt Léonie when she saw from her window ‘a dog she didn’t know.’” The noise of our car announced our approach, and people came to their windows or to their front yard, expecting a familiar face, a honk, and a friendly wave. Bonneval gave us a glimpse into the life of a small town. From Bonneval, we drove to Châteaudun, about 12 miles south. Châteaudun is larger and more affluent than Bonneval; it doesn’t have the small-town atmosphere that Bonneval has. We parked in Châteaudun’s main square, and walked toward the huge château, which is built on a hillside overlooking a river. Of all the chateaus in the Loire valley, the one at Châteaudun is the closest to Paris, and thus the first that tourists come to. The chateau is very impressive from outside, but unfortunately we arrived just after closing time, so we didn’t get to see the interior. We tried to find lodgings, but the hotels we visited were closed for various reasons (because it was Sunday, because it was August, etc.).

|

|

| The chateau at Châteaudun.

We had left Chartres in the morning, and visited three towns in one day: Illiers, Bonneval, and now Châteaudun. Yafei had enjoyed visiting these towns, especially Illiers, which Proust has enveloped in a literary atmosphere. But she had little desire to explore more towns, and see more chateaus. She missed Paris. So we decided to change our plans, cut short our tour of the Loire Valley, and return to Paris. There were many interesting sites in Paris that we hadn’t had a chance to see. And we thought we could find a Paris hotel that was more centrally-located than our previous hotel. But it was too late to drive all the way to Paris, so we headed for the Auberge de Jeunesse in Chartres, and hoped that our previous room would be waiting for us. It was. We experimented with the louvers on the window, and this time we managed to open them, and behold, a vast cathedral was revealed unto our wondering eyes; we could see the cathedral not darkly, but face to face. At night, we walked to the cathedral for a son et lumière show. We also called the Hotel Esmeralda in Paris, and were surprised and pleased to find that they had a vacancy for us for our last two nights. On August 21, we headed for Paris. After a stressful drive into the heart of the city, we returned our rental car, and lugged our bags to the Esmeralda, and up countless stairs to the top floor; since the Esmeralda was built about 1640, it doesn’t have an elevator. In the lobby, one finds the massive beams that old buildings often have. Our room had a good view of Notre Dame. My mother and sister had stayed at the Esmeralda twenty years earlier, and my brother had also stayed there, so it’s a family tradition, as well as a popular hotel, mentioned in all guide-books. Though it was long considered a budget hotel, I’m not sure it still qualifies as “budget”; we paid $100 per night.

|

|

| Notre Dame from the Hotel Esmeralda, with a rainbow behind it.

We spent our first day resting, walking and shopping. We gradually felt more at home in Paris. When we walked by Notre Dame, we didn’t even glance at the cathedral, and we looked scornfully at the tourists who were gazing at it for the first time; though we had been one of them a few days before, we no longer saw ourselves as tourists, but rather as residents of Paris — albeit short-term residents. August 22 was our last full day in France. In the morning, we walked to the Musée Carnavalet, a free museum that focuses on the history of Paris. Its paintings depict Paris social life during various periods, and also the various revolutions that Paris has witnessed. Our favorite exhibit at the Musée Carnavalet was signs — signs that shopkeepers hung out, such as a giant key hung in front of a locksmith shop.9

|

|

|

| À La Tête Noire (At the Black Head)

After lunch, we embarked on a Proustian pilgrimage, visiting the Right Bank addresses where Proust spent most of his life: 9 Boulevard Malesherbes, and 102 Boulevard Haussmann. The Haussmann address is now a bank, and a Proust website said that the bank allowed Proustian pilgrims to see Proust’s room, but the people at the bank said otherwise, and we had to content ourselves with seeing the outside of the building, the neighborhood, etc. If we had more energy, we could have visited Proust’s high school, the Lycée Condorcet, at 8 Rue du Havre. But we had already walked a long way, and we barely had enough energy to reach the nearest subway station, and return to the Esmeralda. That night, we set out for a Left Bank restaurant that was recommended by our guide-book, but on the door was a sign that we were all-too-familiar with: Bonnes Vacances à tous! So we walked past The Pantheon in the direction of a popular shopping street, Rue Mouffetard. Before we reached Mouffetard, we stopped at a restaurant called Le Coq’Agile, which specializes in coq au vin. There, for the only time on our trip, we had a full French meal, complete with hors d’oeuvre (pâte de compagnie) and dessert (mousse au chocolat). We loved it, so when we got back to the U.S., we hurried to the nearest French restaurant. A restaurant like Coq’Agile is cheaper than you might suppose; you don’t pay tax or tip in France (they’re included), and a complete meal is only 10€. If you’re staying in Paris, a good day-trip is Vaux-le-Vicomte, a chateau southeast of Paris. It was built during the reign of Louis XIV, just before Versailles was built, by the same people who built Versailles; one might say that it inspired Versailles. Since it isn’t as famous as Versailles, it isn’t as crowded. Another good day-trip from Paris is the forest of Fontainebleau (there’s also a chateau in Fontainebleau). The cathedral at St Denis would be an easy day-trip since it’s close to the center of Paris; St Denis is famous as the burial place of French kings, and as an important early example of Gothic architecture. Unfortunately, the town is notorious for its high crime rate. On August 23, we took the train to the airport, and made the long journey back home — back to where one rarely hears French spoken, and where one sees no boulangeries (bakeries), pâtisseries (pastry shops), boucheries (butcher shops, meat shops), or charcuteries (sausage shops). © L. James Hammond 2006 |

| Footnotes | ||

| 1. | As Thomas Wolfe put it, “he did not ‘enjoy’ travel — it was a spiritual necessity to him; in some measure it fulfilled a deep hunger in him for knowledge and change, and it awoke him from the lethargy into which he fell after he had been for too long in one place. But if it renewed him, it brought with it also incessant struggle, incessant tumult and disorder.” back | |

| 2. | On the Île de la Cité, not the Left Bank. back | |

| 2B. | According to the scholar Robert Chandler, Dostoyevsky was inspired not by an Italian landscape from the brush of Claude or Salvator Rosa, but rather by Raphael’s Sistine Madonna, which hung in the Dresden Art Gallery. (See The Road: Stories, Journalism, and Essays, p. 76, by Vasily Grossman, commentary by Robert Chandler with Yury Bit-Yunan.)

The phrase “beauty will save the world” can be found in Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, Part III, Ch. 5. back | |

| 3. | Modern Painters, Volume I, Part II, ch. 1, section 7 back | |

| 4. | In 1970, when de Gaulle died, the Place de l’Étoile was re-named Place Charles de Gaulle, but people still use the old name. back | |

| 5. | I think the street runs between the Rue de la Huchette and the Quai Saint-Michel. One might suppose that the street is named after an actual cat, who fished along the Seine, which is nearby. I suspect, though, that it’s named after a shop that used a fishing cat as its symbol/name. back | |

| 5B. | Paris has many smaller museums. The Jeu de Paume, in the Tuileries, was known for Impressionist paintings until the Musée d’Orsay was built in 1986; now the Jeu de Paume has contemporary art. (“Jeu de Paume” means “game of palm”; the building was originally a tennis court, and an early form of tennis was played without racquets, that is, it was played with your palm.) The Petit Palais has a variety of art works, mostly pre-Impressionist; it’s on the Right Bank, near the Grand Palais (both Palais were built in 1900 for the Paris Exhibition), and near the Pont Alexandre III. The Branly museum is on the Left Bank, near the Eiffel Tower, and specializes in the art of indigenous peoples; the Branly has a “living wall” made up of plants. back | |

| 6. | The World as Will and Representation, vol. 2, §3. Pilgrims were known by the scallop/cockleshell symbol on their hat; Shakespeare speaks of, ...his cockle hat and staff, and his sandal shoon. (Hamlet, IV, 5) back | |

| 7. | quoted in Painter, ch. 2, p. 22 back | |

| 8. | Marcel Proust: A Biography, by G. Painter, vol. 1, ch. 5, p. 62. Painter is quoting Daniel Halévy. Click here for a group photo showing Dashiell Hammett standing on far right, with face averted. Raymond Chandler is standing second from left, eyes averted. The people in the group all wrote for a magazine called Black Mask. back | |

| 9. | The first sign in the exhibit said “La Rôtisserie de la reine Pédauque”, and had a picture of the Reine Pédauque. I was reminded of Anatole France’s novel, At the Sign of the Reine Pédauque. But who or what is a “Reine Pédauque”? I poked around the Internet, and found this:

| |